Võ, a path

Võ, firstly a discipline chosen by the practitioner very often by chance.

The person joins a club with the objective of practicing a combat sport, looking for a way of defending himself and possibly maintaining his health.

The rigor of the training will make him realize very quickly that to progress, willpower, hard work, and determination is needed, but above all intelligence.

Each movement is linked to a symbolic representation; the practitioner must search for the meaning in order to better understand the martial art, and above all to know where it will lead him. His attention and perspicacity are constantly solicited.

Each school has its own symbols and emblems. The destined practitioner will, during his practice ask himself what they mean. From here begins a long personal search, history, the study of the classics, philosophy, etc. The practitioner understands little by little, the extent at which culture and tradition impregnate Võ, which has become for him his path.

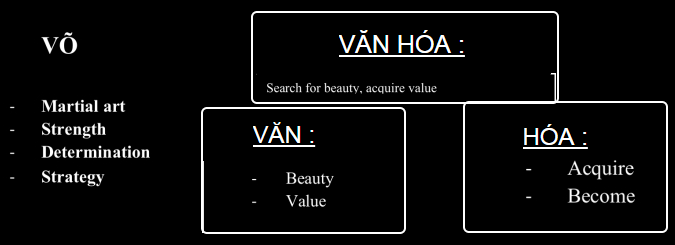

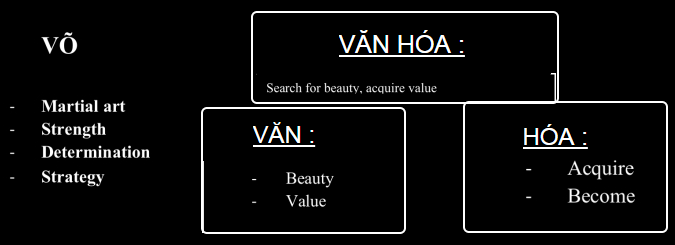

In Vietnam, Võ (martial art) is inseparable from Van Hoa (culture).

Võ and Vãn Hóa allow the person following the path to acquire two types of values which will lead him to the realization.

1. Useful and material values:

Physical practice (external and internal) The TRUE

Virtues: Humanity, equity, integrity etc.

Rites: Simply well-established social uses, urbanity. The GOOD

2.Spiritual values:

Aesthetic, art, everything that touches the spiritual domain The BEAUTIFUL

Truong Mon Andre Gazur

_____________________________________________________________________________

What Is Võ?

The practice of Võ and understanding it, is to differentiate between what is secondary and what is essential, to become aware of one’s potential.

Võ is a path amongst others, a sure path permitting no error. If the work is long and difficult, the adept of this path will know no doubt, he knows where he is going and how he will get there.

Willpower (Chi) is one of his principle qualities.

For the Vietnamese, Võ is a real ideology: martial practice, exercises for good health and longevity, meditation, a healthy lifestyle, culture and tradition, and above all a code of honour.

Võ is not a goal, but a way of rising up, making a success of one’s life.

To the question: ‘Why not encourage daily efforts by making this path more accessible?

You replied: A good carpenter cannot change the plumb line to accommodate a badly skilled craftsman, the Master does not modify the curve of his bow for clumsy shooters. A man of quality draws his bow without unhooking the arrow, which is obvious to the pupil. He stands right in the middle of the right path and those who can, follow him.

Another art that Võ can be compared to is music. In order to perform a piece of music well, the musician must firstly perfect his technique, understand the piece, appropriate it, and finally personalize it. A perfectly performed piece on a technical level doesn’t necessarily make a musician an artist. To achieve this he must have a gift, an essential quality in all artistic expression.

Võ is of this nature, one can devote oneself to practice all one’s life, but to be an artist is something else.

“The artist talks about his art above his technique, someone who is not an artist talks only about his technique.”

Truong Mon Andre Gazur

_____________________________________________________________________________

MASTER – ADEPT

To understand Võ and to love it, one must find a Master. When the pupil has found him, and above all when the Master has accepted him, he must seek his presence incessantly. A Master teaches at all times, as much as in the Võ Dủờng,, as around the table, eating and drinking tea.

We often learn from our master during unusual moments, it isn’t necessary to be wearing a võ Phuc and in a lesson, this is why it is important to be near one’s Master constantly.

A gesture, a word can light up your day and answer a question that has been on your mind for years.

Instruction or rather initiation is given directly, man to man. The exchange between Master and adept is something inestimable, magic, it is a privileged moment or the adept; for he who receives, but also for the Master, he that gives, happy to see his teaching understood, that this adept could be a passer, a Master.

This is why, very often, in a group lesson, the Master seems to be particularly interested in one pupil during a period of time. The other pupils should not feel excluded or jealous. This behaviour on the part of the Master, has nothing to do with affection, but simply that at a precise moment, the Master felt the necessity to correct the pupil, this pupil in particular, because it was at this moment in his teaching that his correction will be beneficial to him.

A few minutes later, it will be the turn of another pupil if the moment has come for him too. It is necessary that certain conditions are met (receptivity, technical level, etc) so that this exchange, this transfer of knowledge takes place and is fruitful.

Therefore, in order to have this opportunity one must be close to one’s Master constantly, in training as well as at his home, a Master is always accessible, available and open like a father for his children, which is where the name Sủ Phu meaning Master and father comes from (spiritual father) different from võ Su, technical Master (expert).

Very often in Asia, pupils (the poorest) live at their Master’s house and participate in daily chores. A Master who isolates himself, moves away from his pupils, isn’t a good Master. In isolating himself, he will be unable to understand when potential problems (relational or other) arise, and he won’t detect them; the harmony of the school may be affected.

Truong Mon Andre Gazur

_____________________________________________________________________________

TRANSMISSION

The Master is not an ordinary man; he is a fulfilled man, a sage.

“The sage transcends the social condition”

Under the influence of this sage, other men will discover and follow the path, and perhaps in turn reach fulfillment.

This is achieved through freedom. Only a free man can achieve this state, he must draw on past experience.

The great fundamental principles, virtues such as humanity, justice, respect, intelligence, and integrity are the basis of all philosophies. The man following the path must make a very particular interpretation.

Also, with each Master, the art evolves, not because it becomes fundamentally different, but in one era, social context etc., by his intelligence, creativity, sensitivity, the master will make it understood by other men. This transmission from man to man allows the art to live on.

When a Master dies, a whole segment of history disappears with him.

Throughout his existence, a Master has often had several adepts, and each of them has taken a part of his teaching at different times. As the teaching of a Master is in constant evolution, each adept is therefore individual. Some will teach and perhaps found their own school, become in their turn passers, Masters.

The adepts that have become Masters will personalize their work and create another style, their style.

This is where the necessity of never taking the name of the Master’s school comes from in Võ, which unfortunately is not respected.

This misconception or disrespect of tradition is the source of disorder and conflict.

The claim of the school’s name by one or several adepts is an aberration which will inevitably lead to failure. No adept, as brilliant as he may be, will practice like his Master. Once the Master disappears, his school disappears with him.

One can say that only the founder of a school practices and teaches the style that he has created, where only he is qualified to designate one or several adepts who can claim, practice and teach his style.

But this recognition only contains value during his lifetime, when the Master dies, it is finished forever. The adept having no longer the Master to teach him, continues his studies alone, and so, personalizes, voluntarily or not, his practice and his teaching.

The style of his Master will disappear little by little or, rather, relive under another form, but, despite the evolution, if this is of quality and respects tradition, one always recognizes the practitioner’s style of origin.

At the death of his Master, an adept who desires to teach could say, for example:

“I was an adept of Master Nguyễn Dân Phú founder of the style Thanh Long”

And not: “ I teach the style Thanh Long “

One knows from where the practitioner comes from, but he can by no means claim the style Thanh Long.

No artist, musician, painter, etc. can re-do what has already been done. If he has talent, he will create in his turn. The man following the path, he whose art is his life, should claim only what he has done himself, his words and his actions commit only himself and suffer no comparison.

Thus the adept who desires to found a school in order to teach his art based on his experience and aspirations should give himself a name that is his own.

However, those who do not have the vocation may continue their practice and teaching under a generic term such as Việt Võ Đạo, Võ Thuật, Vô Cố Truyền, that represent no style in particular but encompass diverse classic aspects of Vietnamese traditional art.

The best he can do is to follow one of his elders who is qualified, because a teaching that is simply technique becomes very quickly limited, and uninteresting, it transforms itself rapidly into a simple combat sport.

Formerly, sages applied their knowledge and qualities in teaching, philosophy, politics, the running of the country, and this for the good of the community.

The sage only has one goal, which is to train free, integrated and useful men; from where comes the Việt Võ Đạo motto:

‘Be strong to be useful’

This education allows them to find meaning in their lives, to be something different, to acquire in their turn a certain nobility.

Sages attracted men of value by their honest and generous teaching.

A king said:

‘Give me one single minister, provided he be honest’

But to deserve this minister, the king must himself be irreproachable and a person worthy of respect.

“The truth is found in sincerity, whoever is not sincere cannot act upon others”

Trăng Tư

If the Master speaks, his actions should match up to his discourse. Such a Master will without any doubt attract adepts; in the opposite case, the Master who deceives his adepts will be abandoned. Hence, would the love that his adepts had for him be transformed into hate because of the harm he did them?

“Skillful speech, a deceitful face have little humanity”

There is no lack of examples in the history of martial arts. Many renowned schools have crumbled and been discredited by the behaviour of their Masters who have become authoritative, egocentric, and selfish with little concern for the happiness of their adepts, replacing TÌN (integrity, faith, trust) with an oath (constraint) in order to ensure the submission of the adept.

If a Master loses his adepts, it is his adepts that have lost their trust in him.

“Tradition is the vehicle of Martial arts.

It is founded on the relationship of trust with the Master that allows to transmit and uphold a thriving practice.

Truong Mon Andre Gazur

_____________________________________________________________________________

EVOLUTION

A Distinction should be made between a combat sport and a traditional martial art.

In a combat sport (various boxing styles, Judo, etc.) the technique remains unchanged through generations.

The approach is very pedagogical. In all countries, the techniques and applications remain identical.

No teacher introduces his personality and no research is carried out, unless it is in the regulations, the objective being the development of the masses and competition.

Certain practitioners are attracted to these disciplines for exactly these reasons. Here we speak of a sporting movement; not a school.

This was, moreover the wish of their founders; Master Kano for Judo; Master Nguyên Lộc for Vovinam; etc.

Their project was to extract sufficiently simple techniques from traditional martial arts that would be accessible to the highest number of people, compile them, and codify them, in order to make an educational system, physical and moral, but above all applicable in competition.

Traditional Võ, on the contrary, is in constant evolution because art cannot be static. There exists a multiple of schools and therefore a multitude of Masters. Each of these Masters owes it to himself to bring the fruit of his research to the art; that which is static will finish by becoming distorted, impoverished and disappear.

Teaching, or rather initiation is done from Master to adept.

We know that in the past Masters were great voyagers, and didn’t hesitate in leaving their home towns, their students.

In this need for travel, for change, we can see a quest for freedom, the necessity to devote himself entirely to research, to the elaboration and application of new theories and other places. But especially, with other men because very often students don’t understand the change, evolution in their Master’s teaching, and become a hindrance to this need, to this quest.

On the other hand, those who understand don’t hesitate in following their Master in his peregrinations.

These voyages also served as occasions for the Masters to meet and exchange with other experts, other scholars.

This is how styles have merged and evolved. A man of art cannot be satisfied with stagnation, routine.

In Việtnam, a freedom loving man of art, an artist, an adept of the path, often says:

“Tôi úa hoạt Động»

“I love movement”

Success is in movement

Today, this conception is difficult to accept for westerners who are used to organizing everything, itemizing, classifying etc. Some adepts are disorientated by the evolution in the Master’s teaching. Not understanding, they finish by abandoning the practice or turning towards combat sports precisely for their easy access and sporting goal (competition, etc.).

These adepts are right, not destined for traditional practice; they will be wasting their time.

Contrary to preconceived ideas, adepts of competition, even in the great sports federations (karate etc.) only represent a small percentage of practitioners (approximately 10%).

Slogans like: fraternity, respect, surpassing oneself, human exchange, etc., borrowed from traditional disciplines do not hide hypocrisy, stupidity, violence, caused by all sorts of competition, from the protagonists as well as from the spectators.

Over mediatization of events, the star making of sportsmen, fascinates the masses, infantilizes them, and turns them into imbeciles. Television, the preferred media source, insidiously makes its adepts avid consumers.

In martial arts, the ambiguity resides essentially in the fact that a large number of practitioners, teachers and decision makers do not know the tradition (or the misappropriation) and confuse traditional martial art and combat sport, school and sporting event.

To understand, one must have received the teaching of a true Master in the heart of an authentic school.

The aim of the teaching in the heart of a traditional school is that each member can progress and flourish.

No title is at stake. Technical exchanges or combats are carried out with a partner, a fellow student, a man following the same path (Đˋông Đạo).

In a combat sport, the objective is to win a title, and to do this one must eliminate, fight the adversary, there is only one winner.

“Art is what permits a man to reach his full potential amongst others, whereas sport permits a man to reach his full potential at the detriment of others”

If all practice is respectable, one must not, from hereon in, maintain ambiguity between sport and art.

Truong Mon Andre Gazur

_____________________________________________________________________________

VÕ – EFFECTIVENESS

Is Võ a really effective means of defense?

Yes, without a doubt, if it fails, it can only come from the practitioner (lack of experience, weakness, etc.) The technique is never questioned.

Equally, a musical instrument can produce, depending on its user, marvelous or horrible sounds, refined or crude. The instrument doesn’t make the musician, like the clothes do not make the man, and the vô phục the practitioner.

The adept of Võ must firstly, absolutely, work towards the effectiveness of his technique, above all, to avoid falling into any illusion.

A traditional school trains the practitioner in a particular technique (style), the movements are self-sufficient.

Weight training, strength, resistance, flexibility, elasticity, are acquired through these movements, there is no need to look to complete one’s martial technique with all sorts of gymnastic exercises (push-ups, abs, jogging, etc.)

In certain styles like the Thanh Long, excessive muscle development (chest) can hinder the practitioner in the execution of certain movements (circular movements in the axis, hammers, claws, palms, fists, elbows, and special kicks).

The study of respiration, concentration and above all the implementation of strategy by intelligence refine the practitioners training.

This first step will provide the practitioner with the confidence (mastering) which will allow him to tame his fear and thereby gain his freedom. Fear diminishes man, and can reduce him to servitude.

All these aspects of the practice are represented by the symbol Võ that we usually translate as: martial art.

It is very difficult to translate an ideogram with a simple word but if this had to be done it would perhaps be: strategy, because this word largely overcomes the notion of combat.

Strategy implies an idea of reflection, intelligence, how to manage a situation or a conflict avoiding confrontation at all cost because either way the risk is mutual.

In Vietnamese, one says:

“ Lạt mếm buộc chặt”

The thinnest thread ties the most surely

In this way, in martial practice, whether it be with bare hands or traditional arms, while carrying out the quyến, one never begins with an attack, an aggressive movement, but by a blockage or a symbolic non aggressive gesture, of a refusal to fight, to engage the adversary not to fight.

“Võ is above all defensive”

The ideogram Võ well expresses this idea.

: The spears stop the enemy.

A quyến starting with an aggressive movement is a bad quyến, it shows that its creator has not understood the sense of the martial culture.

On the other hand, athough the first movement symbolizes the will of non-aggressiveness, a practitioner of traditional martial arts still must make his freedom respected.

“Hence, this first movement is never carried out rearwards, but either forwards or on the spot.”

In this way the practitioner shows his determination. A good practitioner refuses to have his liberty taken from him, refuses to flee his responsibilities, if confrontation becomes inevitable, then it will take place; this applies to martial practice, this applies to all men’s lives, to face difficult conflictual situations and manage them with strategy, effective intelligence.

One finds in the search for personal elevation, this decisiveness, the will to never step back, to always move forwards, to work, to incessantly perfect oneself, to evolve.

Truong Mon Andre Gazur

_____________________________________________________________________________

MARTIAL ART AND FILIAL PIETY

To devote oneself to art does not in any case necessitate being mystic, tormented, or even insane.

In the western countries, we easily imagine famous artists, musicians, sculptors, actors as depressive, alcoholic,

drug addicted, and suicidal beings.

Must one be mentally tormented to create? Certainly not!

In Asia the artist (calligrapher, painter, Võ Sù etc.) is a healthy man, fulfilled, serene, enjoying life. Whatever his

discipline, he cultivates his body. In order to better create, he devotes himself to respiratory techniques and

meditation. Physical activities are essential for all arts.

Filial piety (one of the classic books) dear to all Asians, advocates the respect of our body in relation to our parents

who conceived us, who passed on their genes (ancestral energy), who took care of us when we were children, then,

later educated us. This filial piety impregnates all men and influences their behaviour, respect of ascendances, but

also of descendants.

Master Phu said:

“In order for a child to love his parents he must be proud of them”.

In Vietnam, a man never forgets his parents or from where he has come from. In Võ (Thanh Long origin), this

remembrance and respect is translated at the end of each quyến by the seven punches given symbolically as a

reminder of the tradition*:

Thái Cực, The Grand Absolute

Thiên, The sky

Địa, The earth

Thầy The Master, the guide

Cha The father

Quê Hùòng The native land, origin of one’s path

Đông đạo Co-adepts (brothers in martial practice)

The seventh is particularly important since it is among our co-adepts that we are raised, a man alone is nothing. A

cry is emitted during the execution of these seven punches.

In the same way, a man knows what he owes his children.

“The fear of harming my son, corrected my gambling, my wine consumption, saved the delicateness of my vanity

and the spurs of my anger a thousand times; I owe him my patience and my friends.”

To respect and maintain one’s body does not prevent one from living a full life, the Võ practitioner is not an ascetic

(except in some schools that integrate Taoist or Buddhist obedience).

Võ Sù are generally happy personages endowed with a strong personality. They are greatly concerned with

independence and liberty. A Võ Sù does not indulge in the ordinary.

One day I was visiting an old Master of Hà Nội. As was the custom, the Vietnamese friend accompanying me

helped our host’s wife to prepare tea and cut up some fruits. She shared her feelings with my friend:

“A Võ Sư is very difficult to live with because he likes freedom, but at least, with him one is never bored. “

Truong Mon Andre Gazur

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()